The Kentucky Steward LLC, R. M. True

“You can lead a horse to water, but you can’t make him drink.”

The Kentucky Steward testifies to the House Standing Committee of Natural Resources and Environment in Opposition to SB 89

On March 12, 2025 The Kentucky Steward testified to the House Standing Committee of Natural Resources and Environment in opposition to Senate Bill 89 (SB 89) which proposes to redefine, and thus deregulate, environmentally protected “waters of the Commonwealth”— to exclude “non-navigable” waterways, ephemeral streams, ponds, lakes, and groundwater.

Fellow stewards can view The Kentucky Steward’s full testimony here.

By deregulating “waters of the Commonwealth”, industrial corporations in industries like mining, power generation, hazardous, solid, and special waste landfills, underground storage facilities, large-scale agriculture operations, and various chemical processing plants in some instances will no longer be required to monitor the water quality of their effluent and or leachate, or directly downstream of their effluent or leachate.

Given the implications of redefining “waters of the Commonwealth”, The Kentucky Steward performed extensive research to characterize the history and in-situ presence of Kentucky groundwater contamination, specifically contamination caused and perpetuated by industrial corporations and their influence on Kentucky stakeholders’ drinking and process water supply.

Brief overview of The Kentucky Steward’s Review of Historic and In-situ Industrial Contamination of Kentucky’s Groundwater, as provided to the House Committee of Natural Resources and Environment

Research included the analysis of over 637,000 groundwater readings available to the public via the Kentucky Geological Survey’s (KGS) Groundwater Data Repository from 1975 to 2024; specifically analyzing 100 contaminants (i.e. metals, VOCs, SVOCs, PCBs, PFAS, Pesticides, Herbicides, Inorganics, and Nutrients) through a variety of empirical considerations and a self-established severity scale that serves to characterize the most severe contaminants that pose environmental and community health risks to Kentuckians.

- Note: The KGS Groundwater Depository was initiated in 1990 by the KGS under KRS 151.035 to maintain and make accessible to stakeholders all available groundwater quality data collected by KGS, KDOW, among other Interagency Technical Advisory Committee on Groundwater (ITAC) members.

Of the 100 contaminants, 60 pose significant to extreme health risks to Kentucky stakeholders. Health risks that range from skin and respiratory irritants to organ and central nervous system damage to tumor development and cancer.

- The 60 primary-concern contaminants maintained historic and actively occurring concentrations in groundwater that exceed EPA established Maximum Contaminant Levels (MCLs) by as much as 500,000,000% (i.e. the cancer-causing industrial solvent 1,2,3-trichloropropane), as well as purporting average concentrations of up to nearly 900,000%. One exceedance of an MCL from a local standpoint is concerning; however, The Kentucky Steward’s research implemented several empirical analyses that fully characterize contamination industry-wide and statewide overtime rather than simply reporting outlier metrics. For instance, while there was a one-time exceedance of 500,000,000% of MCL for 1,2,3-trichloropropane, of the 3,148 non-zero readings, all 3,148 exceeded an MCL of 0.000005 mg/L by an average of ~900,000% (~0.045mg/L). Such considerations influenced a greater severity score, as opposed to single outlier metrics, causing 1,2,3-trichloropropane (among several other carcinogenic contaminants) to score a 100/100 on The Kentucky Steward’s severity scale.

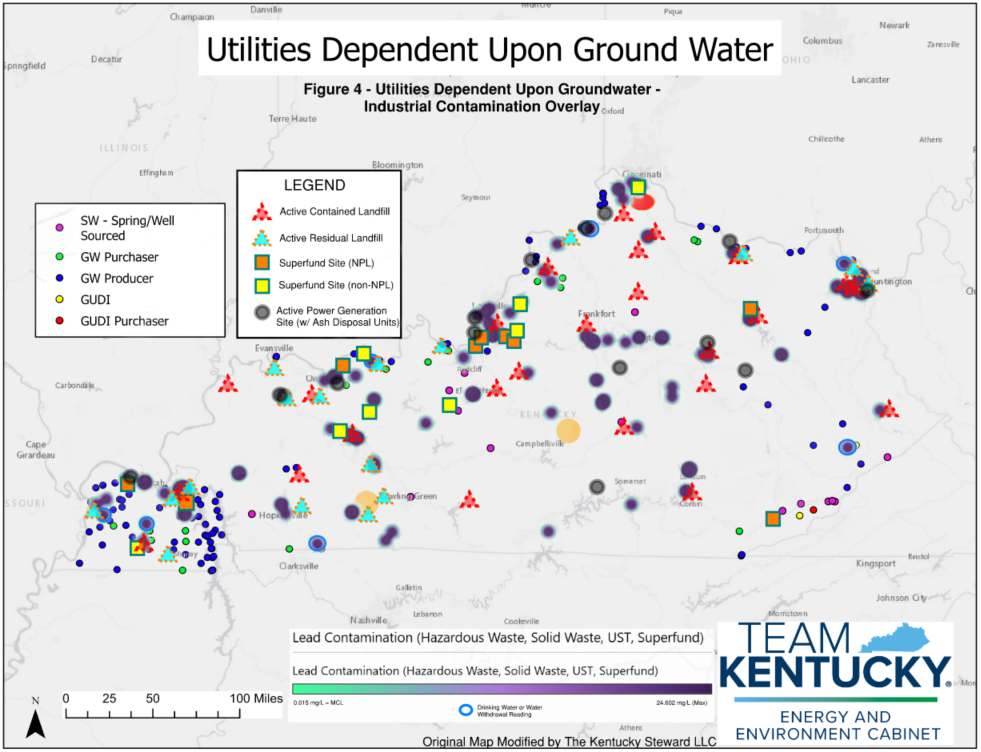

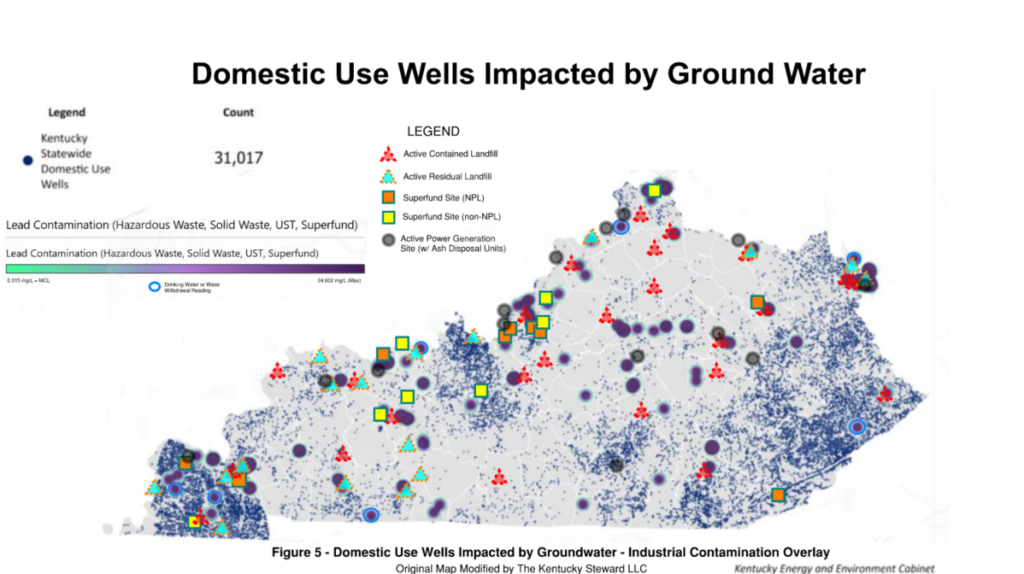

- Fellow stewards are encouraged to view Table 1 in the attached research report (pgs. 9-10) to view the empirical breakdown of the other 99 contaminants. There you will see more commonly recognized contaminants like arsenic, lead, and PFAS. Several visuals were provided in the report to characterize industrial contamination exceeding MCL in close proximity to drinking water supply sources. See snippets of Figures 4 and 5 below for example. Additionally, given the geologic diversity of the state, Figure 6 (pg.19) was developed to characterize industrial contamination in areas of hydrogeologic areas of groundwater sensitivity.

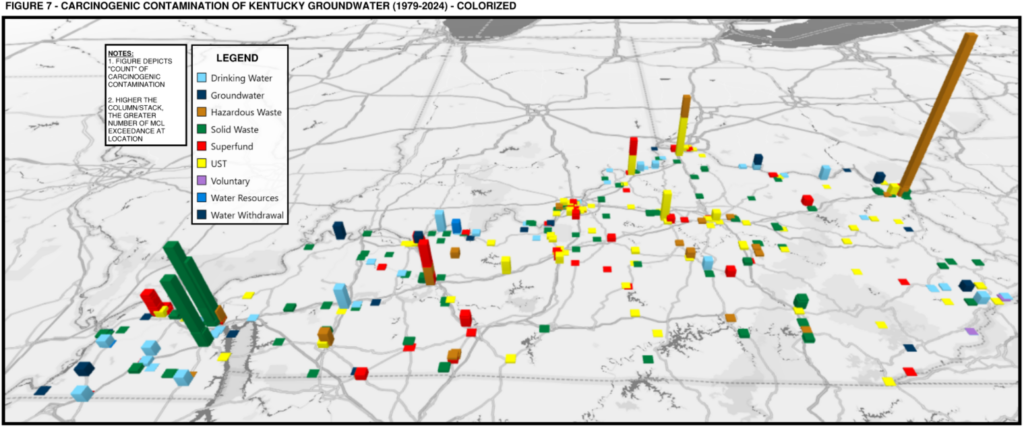

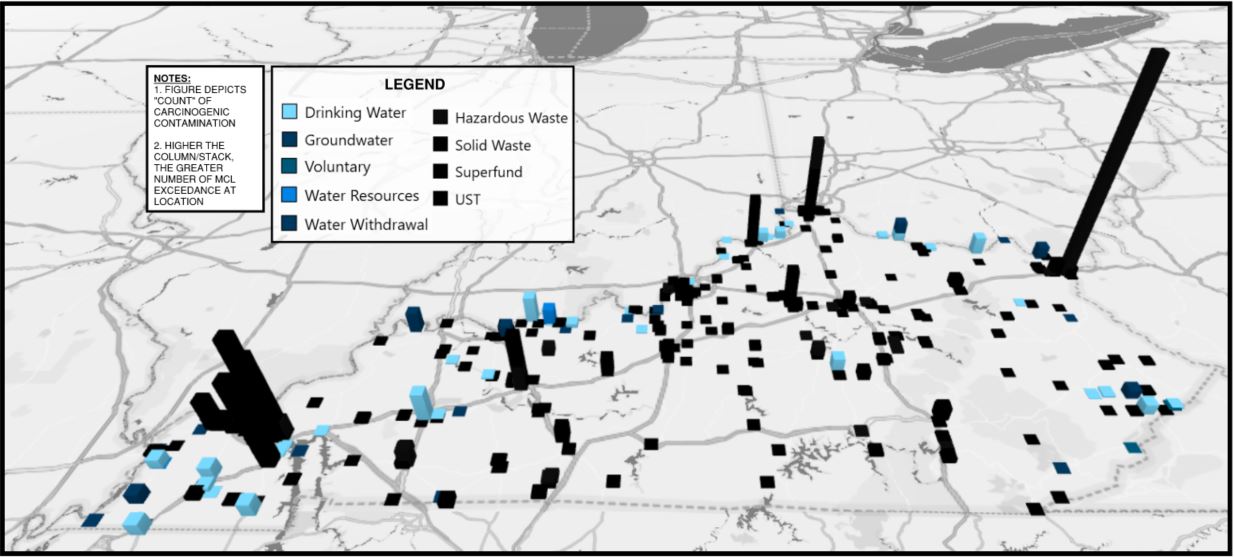

- In preparation of The Kentucky Steward’s testimony, an entire subsection including two figures were specifically included in the report (version 2) as they offer the most conservative lens in characterizing the most severe health risks to Kentucky stakeholders due to industrial contamination. See snippet of Figure 7 below, which reflects nearly ~19,000 instances of carcinogenic–or cancer causing–contaminants exceeding MCLs from 1979 to 2024. Figure 7 also characterizes the regulatory program distribution of contamination. Namely, point source contamination sites like Hazardous and Solid Waste Landfills, Superfund sites, and Underground Storage Tanks. The remaining regulatory programs, Drinking Water, Water Resources, Groundwater, and Water Withdrawal, represent stakeholders’ drinking water supply and process water for various commercial and industrial use. The primary takeaway Figure 7 offers is the direct correlation of industrial carcinogenic contamination and contamination detected in drinking water and process water resources. The two groupings of regulatory programs–point source contamination sites and groundwater stakeholders intend to use–are in close proximity to one another. Figure 8 (prefacing this essay) was developed to reflect a clearer contrast between point-source contamination sites (colorized as black) and non-point source contamination sites (sites directly affecting Kentucky stakeholders; colorized as variations of blue). When viewing Figures 7 and 8 it is important to note column height correlates to the number of readings of carcinogenic contaminants that exceeded respective MCLs. Thus, the greater the column height, the more instances of carcinogenic contaminants exceeding MCLs at that specific site.

- A final note regarding the research: the groundwater data is practically limitless in terms of the ability to characterize groundwater contamination, especially to characterize the impact industry maintains on stakeholders. Given the legislative fast-tracked schedule, the report was fast-tracked as well. With this said, there is limitless opportunity to generate additional figures, interpret the data from a local-standpoint, and include 200+ other contaminants in addition to the 100 considered in this research. All of these opportunities may be pursued by The Kentucky Steward in the upcoming weeks, but ultimately yield the same conclusion:

Kentucky maintains a historic and present systematic, industry-wide contamination of its groundwater. This reality has taken place under more conservative regulatory requirements mandated by the state of Kentucky than those required by the EPA (federal government) itself. Thus, maintaining water quality monitoring and reporting requirements is essential to protecting public health. The data presented summarizes the potential consequences of weakening regulatory oversight, particularly for carcinogenic contaminants that continue to exceed MCLs at alarming rates as well as magnitudes. Sustained monitoring remains critical to identifying contamination trends, mitigating risks, and ensuring the long-term stewardship of Kentucky’s groundwater resources.

Fellow stewards are encouraged to read The Kentucky Steward’s full research report embedded below. Click here to download The Kentucky Steward’s full research report.

The House Standing Committee response, or lack of response, to The Kentucky Steward’s research and other organizations’ testimonies

Unfortunately, The Kentucky Steward’s objective research, in addition to other testimonies, were only acknowledged by a handful of representatives of the House Standing Committee whether via replies to The Kentucky Steward’s emails or via vocalizing their concerns during the house committee hearing. The Kentucky Steward LLC would like to personally commend house representatives McCool, Moore, and Watkins for their consideration of the health of their constituencies. The remaining members of the committee either offered no commentary, or acknowledgement of either historic or actively occurring contamination of their constituencies’ groundwater resources.

The House Standing Committee of Natural Resources and Environment, when provided information regarding the widespread contamination of Kentucky’s greatest natural resource and most important component of the environment and human life, did nothing.

“You can lead a horse to water, but you can’t make him drink.”

Well, next to nothing. The house standing committee did, however, pat themselves on the back by offering an amendment to SB 89; revising “waters of the Commonwealth” to include, in addition to navigable waterways: “sinkholes with open throat drains”, “naturally occurring artesian or phreatic springs, as well as any other spring used as a source of domestic water supply”, and “wellhead protection areas.”

Although, the back-patting is curious considering the amended SB 89 still sacrifices groundwater protection for tens of thousands of private groundwater wells, several thousand domestic use wells, and non-navigable surface waterways not located in close proximity to prominent springs or wellhead protection areas. “Sinkholes” as an inclusion is suspect as it will be difficult to enforce, and there are countless “springs” in Kentucky, yet only several dozen notable “springs” documented within the Kentucky Energy and Environment Cabinet’s resources (of which many are not in close proximity to point-source contamination sites), and “wellhead protection areas”–while a necessary inclusion–account for a relatively small surface area in Kentucky.

In short, the amended SB 89 fails to protect Kentucky stakeholders dependent upon groundwater for drinking water, industrial and commercial, and agricultural water supply.

The Kentucky Steward’s closing statement of its testimony comes to mind:

“Redefining “waters of the Commonwealth” to exclude “groundwater” specifically will not only bring about unprecedented environmental and community health fallout (perhaps beyond remediation); it will redefine Kentucky as a Commonwealth; and it will redefine what it means to be a Kentuckian.”

Without “groundwater” specifically included in “waters of the Commonwealth”, hundreds of thousands of Kentuckians pay the price, in terms of health and added treatment costs. Both of which are not a matter of “if” but “when” and “how much”. The costs are limitless, the costs are inevitable.

Just hours following the hearing SB 89 was brought to a house floor vote and passed 69-26. Of the 21 House Standing Committee of Natural Resources and Environment voting members, only 5 voted no: Representatives Chester-Burton, Hancock, McCool, Moore, and Watkins.

A day later, the senate floor passed SB 89 31-7.

Despite outcry from stakeholders and objective research characterizing industry’s historic and active role in contaminating Kentucky groundwater—especially groundwater utilities, domestic wells, and private wells depend upon—both legislative groups overwhelmingly passed SB 89.

“You can lead a horse to water….”

So it goes.

Fellow stewards, what happens now?

The Kentucky Steward has dedicated itself to working alongside other state organizations like the Kentucky Resources Council, Kentucky Waterways Alliance, and Kentucky Conservation Committee (to list a few) to further educate house representatives and senators who voted YES thus far, in addition to educating Kentucky stakeholders statewide. Offering The Kentucky Steward’s objective conclusions regarding Kentucky groundwater contamination and the influence industry maintains on stakeholder drinking water and process water supply to the uninformed is priority number one. With this said, fellow stewards, please share this essay and linked research report in any capacity you can.

Additionally, The Kentucky Steward intends to contact utilities dependent upon groundwater, private well owners who either maintain a history of dealing with groundwater contamination (or others who aspire to maintain the health of their groundwater), and wastewater municipalities like Louisville Metropolitan Sewer District (MSD) to enroll them in our fight–whether vocalizing their concerns or signing a petition maintained by Kentucky Waterways Alliance.

Ultimately, there are numerous ways to achieve our goal of properly stewarding Kentucky’s “waters of the Commonwealth” as currently, and appropriately, defined. In the following weeks, fellow stewards are encouraged to be bold and vocal on the issue and to further their education on the impacts of SB 89. Proponents of SB 89 have labeled the bill “pro-industry”, citing the “necessary cutting of regulatory red-tape”. It is of the opinion of The Kentucky Steward, an outright pro-industry, pro-worker, pro-coal organization, that this label both severely ignores the environmental aspects and health risks introduced with the bill, and exaggerates the “pros” afford to Kentucky industry–which amount primarily to streamlined permitting, and relatively small annual savings regarding water quality monitoring and reporting.

Can a bill be “pro-industry” if it will inevitably lead to environmental and community fallout? How long until the surface waters affecting aquatic life, the health and biodiversity of countless ecosystems, and recreation affect stakeholders working in said industry? How long before industry-workers dependent upon groundwater discuss symptom after symptom with their doctors on their behalf, their spouse’s, or their children? Industry without healthy workers is no industry at all. Who will grab a pickaxe and man equipment in the mines? Who will operate power generation plants? The strength of Kentucky industry is predicated and perpetuated by the health and presence of its workers.

Kentucky has long embraced and represented a strong-worker persona; and perhaps we are strong because many of our industry jobs cannot be performed by computation, AI, or robotics. There has been and will forever be real, stewardly Kentuckians in uniform throughout the state providing unrivaled service to local and greater communities and their families. Senate Bill 89 places corporate profits (which would fatten, ironically, by negligible margins) before Kentucky industry workers and all other Kentucky stakeholders dependent upon groundwater and surface water–as a means to maintain their culture, livelihood, and health.

There is likely superfluous and unnecessary regulatory “red-tape” that needs cutting. The permitting process, of course, should be more streamlined. Industries that observe little (x<20% of contaminant MCL for example) to no contamination should benefit from relaxed monitoring and reporting requirements, as well as potentially receive federal and state tax credits in response to the effective infrastructure utilized on site and in their groundwater protection plans.

Namely, there should be incentives and benefits afforded to industries that provide services to the state WITHOUT contaminating its waters, rather than affording industries a means to provide the exact same service but at the expense of contaminating state waters.

SB 89 achieves the latter. Elected officials of Kentucky should work hand in hand with one another, on behalf of their constituencies, to enact policy that improves industry without sacrificing the health of Kentucky’s greater environment and the communities it fosters.

In The Kentucky Steward’s local communities like Trimble County and Henry County, specifically, there are countless stewards–many of which are industry workers–who deserve representation. With this said, The Kentucky Steward looks forward to discussing its research and the impacts of SB 89 to stakeholders with Senator Tichenor and Representative Rabourn, both of which voted YES on SB 89, with Senator Tichenor, herself, sponsoring the bill.

Kentuckians have less than two weeks to act in this regard.

Thus sounds the call for all stewards across the state to ensure SB 89 is not passed into law. If we are to fail, and should Governor Beshear’s forthcoming veto be moot given the House and Senate’s inevitable override veto, The Kentucky Steward offers an amendment to the infamous phrase following the passing of SB 89:

“You can lead a horse to water, but

you can’t makedon’t let him drink.”

The Kentucky Steward’s Review of Historic and In-situ Industrial Contamination of Kentucky’s Groundwater, as provided to the House Standing Committee of Natural Resources and Environment (download link below)

steward the state!

Leave a Reply